The summer of 1932 cast a unique light on the quaint coastal town of Ogunquit, Maine. Anticipation crackled in the air, a buzz unlike the usual rhythm of crashing waves and creaking lobster traps. This wasn’t a season for tourists seeking lazy afternoons on the beach; this was a pilgrimage for an astronomical spectacle: a total solar eclipse.

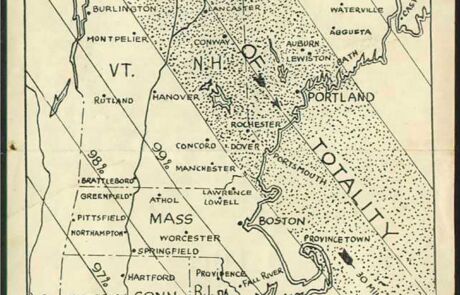

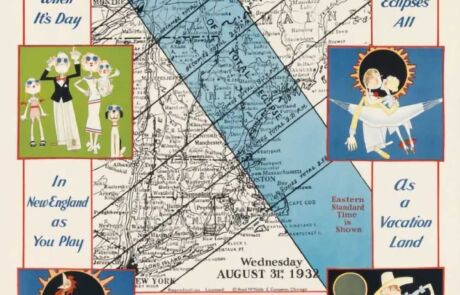

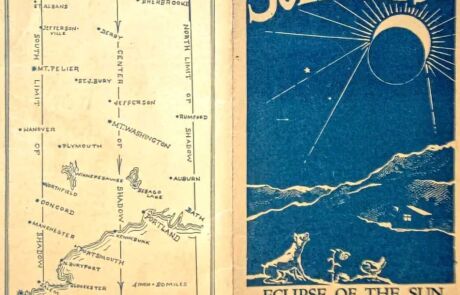

This celestial event, cutting a diagonal swath through New England from Montreal to Provincetown — with the path of totality passing directly over Ogunquit — stirred anticipation among locals and visitors alike. Among the throngs in Ogunquit to witness the sun’s spectacular vanishing act was summer resident and artist Charles H. Woodbury.

Woodbury wasn’t your average eclipse chaser. He was the individual most credited with initially establishing and giving momentum to the Ogunquit Art Colony, a thriving artist community that took shape during the late 19th century. The Ogunquit Art Colony played a crucial and well-documented role in the development of American art. Artists at the colony often painted en plein air, capturing the natural beauty of the coastal landscape.

Woodbury, with his Ogunquit Summer School of Drawing and Painting, helped shape the town’s enduring cultural identity. In 1928, Woodbury, alongside Gertrude Fiske and other prominent artists, founded the Ogunquit Art Association (OAA), Maine’s original artists’ group.

RELATED: The Ogunquit Art Association is still thriving to this day at Barn Gallery in Ogunquit. It has attracted a prestigious list of juried artist-members over nearly a century, embodying the enduring legacy of the Ogunquit Art Colony. Through the fluctuating tides of artistic activity in Ogunquit, the Barn Gallery and the Ogunquit Art Association have remained steadfast, keeping the flame of the original Ogunquit Art Colony burning bright.

Learn more about the Barn Gallery 2024 Schedule: barngallery.org/2024-season

CONTINUE READING BELOW 1932 Solar Eclipse Ephemera Gallery…

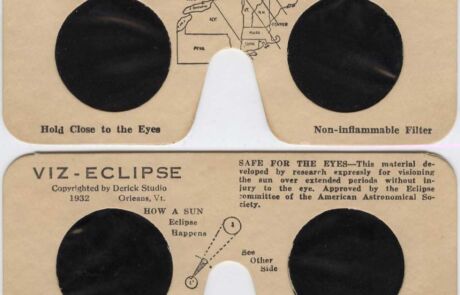

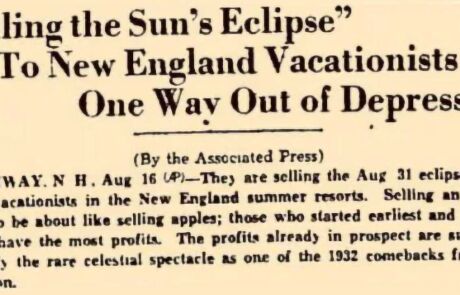

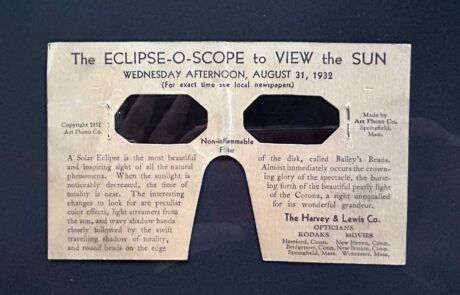

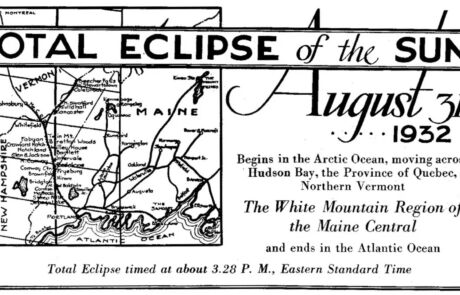

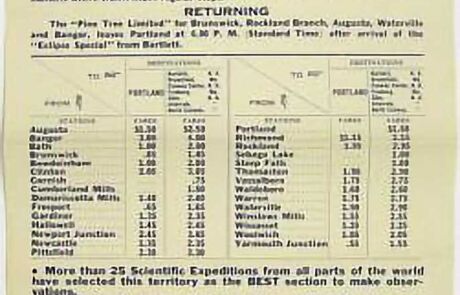

As August approached, New England was abuzz with eclipse fever. Newspapers splashed headlines about “eclipse packages” and special trains ferrying eager skywatchers. The Great Depression cast a long shadow, but the eclipse offered a fleeting escape, a chance to witness nature’s grand drama.

“The total phase begins with the sweep of the moon’s shadow over the earth, just like the coming of a great storm,” reported the Exeter News-Letter. “This shadow travels from west to east with a speed of 1500 miles an hour. As the sun finally disappears its eastern edge is sometimes broken up by bright patches of light. The sunlight creeps through the lunar valleys and produces only for an instant, the ‘Baily’s Beads,’ as these light flashes are called.”[1]

“Hotels and boarding houses will be taxed to capacity, and many will doubtless prolong their stay over the eventful day. For dwellers in Boston and other points out of the belt of totality, there will be special train service.”[2]

Almost everyone was making plans to head to the path of totality for the eclipse to witness this once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon.

Woodbury, however, possessed a different kind of curiosity. His son, David O. Woodbury, described him as having a “remarkable eye-skill,” and on this momentous day, Woodbury intended to put it to a unique test. Woodbury isn’t interested in painting the eclipse itself. Instead, he’s brewing a bold artistic experiment.

Woodbury, a man who reveled in the play of light, envisioned capturing the eclipse’s effect, not on the sun, but on the landscape itself.

On that fateful August 31st, Woodbury didn’t set up his easel facing the sky. Instead, with his back to the spectacle, he positioned himself facing a rocky outcrop. With six pochades (portable easels) lined up and his paints at the ready, he embarked on a rapid-fire painting session, capturing not of the sun’s disappearance, but of the dramatic shift in light and shadow that bathed the landscape during the celestial event.

Woodbury’s son, David O. Woodbury, recalled his father’s fascination with the eclipse, witnessing him paint with fervor as the landscape transformed before his eyes.

In 1932, I watched him in fascination as he painted six pictures of the total solar eclipse in less than two hours,” stated David O. Woodbury. “Only one of them was done during totality, which lasted about fifty seconds. They were small panels, to be sure, but they gave an accurate record of the extraordinary events of color and shifting light that spread over the sea and shore as the sunlight faded and the reflected sky light from the sea horizon took command… The only eclipse pictures I know of that did not include the vanishing sun. He had kept his back to it all the time. What my father wanted from that exercise in swift recording was a meaningful explanation of the curious sense of doom that marches across the world ‘when the sun blots out at noon.’ He got it, unmistakably. He captured that rare event in motion, moving inexorably forward to destroy the familiar stability of the everyday world. No artist could possibly have done it who could not keep up with the changes of light and form, the rapidly failing brilliance and the shadows that moved across the spectrum rather than across the land.[3]

“He was fascinated with the play of light,” stated Woodbury’s grandson, Chris Woodbury. “In 1932, there was a total eclipse of the sun in Ogunquit. He painted six pictures to show the changing of the light (during the eclipse), the different stages of light. He painted very fast. ‘You must get this before the shadows move and the colors change’, he told his students.”[4]

As usual — he found a new approach. While other painters carefully sketched what was left of the sun, around the moon’s limb, Father turned his back on it and painted a cliff and its inverted shadows, proving that all were warm, and the sky light cold. It was an invaluable contribution to science and the extraordinary panel, all six sketches lined up together, hangs now in the Adler Planetarium and Astronomical Museum in Chicago. An announcement by Philip Fox, Director, reads on the frame: ‘A great artist’s impressions of light and color changes during a solar eclipse. Paintings by Charles H. Woodbury made at Ogunquit, Me., during the eclipse of 31 August, 1932.’[5]

The resulting series, a unique contribution to eclipse paintings, reflects Woodbury’s artistic vision. Each canvas, labeled with the specific time (“2:30. Before the Eclipse.” “3:00. Half Hour before Totality.” “3:30. Totality.” “3:45. Quarter Hour After totality.” “4:30. After the Eclipse.”), offers a glimpse into the dramatic transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary. We see the warm hues slowly draining from the scene as the moon devours the sun, replaced by an ethereal, cool light emanating from the horizon. These paintings aren’t just mere depictions of an eclipse; they fully expose the acumen of Woodbury’s keen eye for the subtle dance of light and a scientific study translated onto canvas.

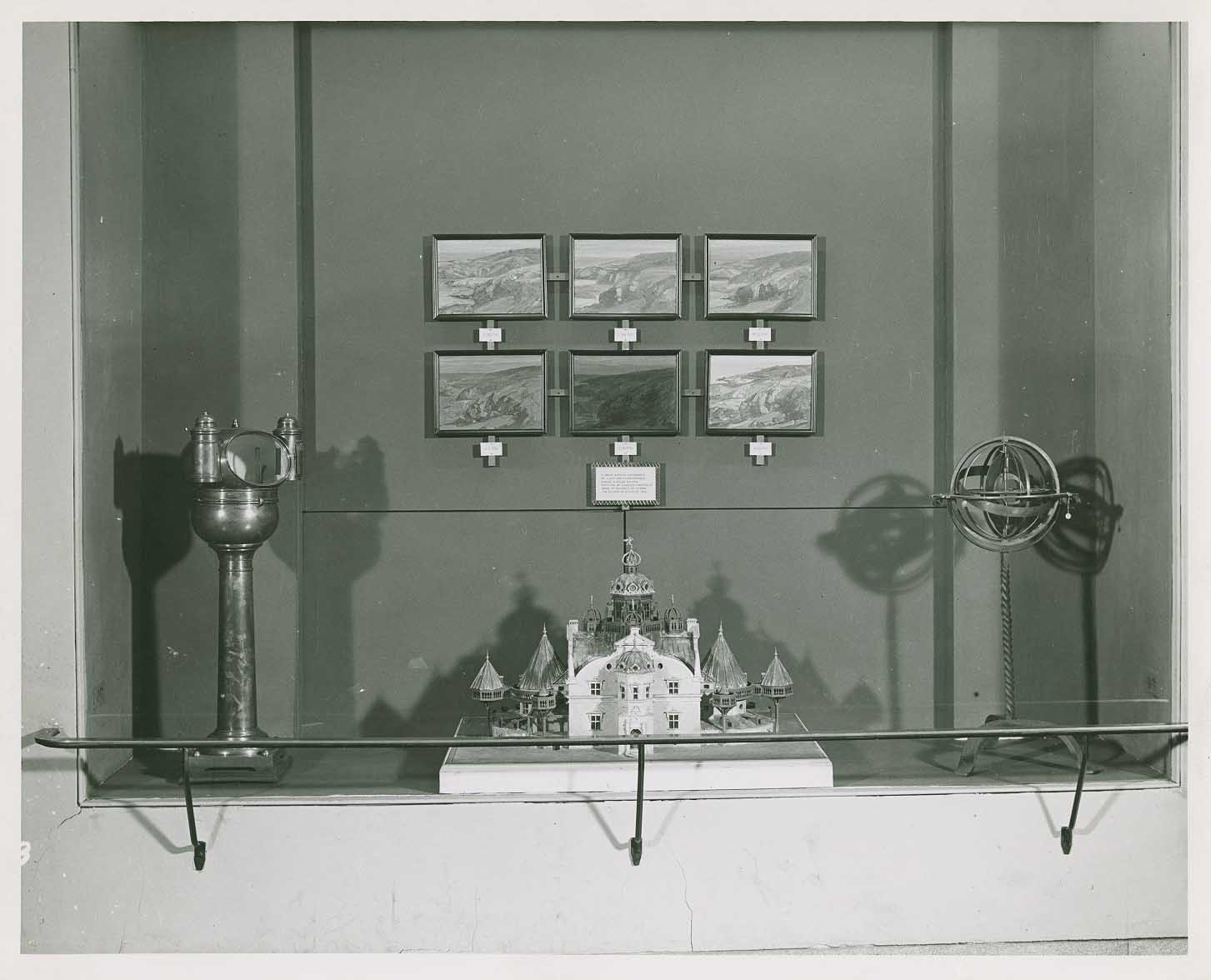

Close-up view of six landscape paintings painted by Charles Woodbury during an August 1932 eclipse. Courtesy: Adler Planetarium

Close-up view of a display case of historic scientific instruments on the mid-level of the Adler Planetarium. Display case includes six landscape paintings painted by Charles Woodbury during an August 1932 eclipse. Courtesy: Adler Planetarium

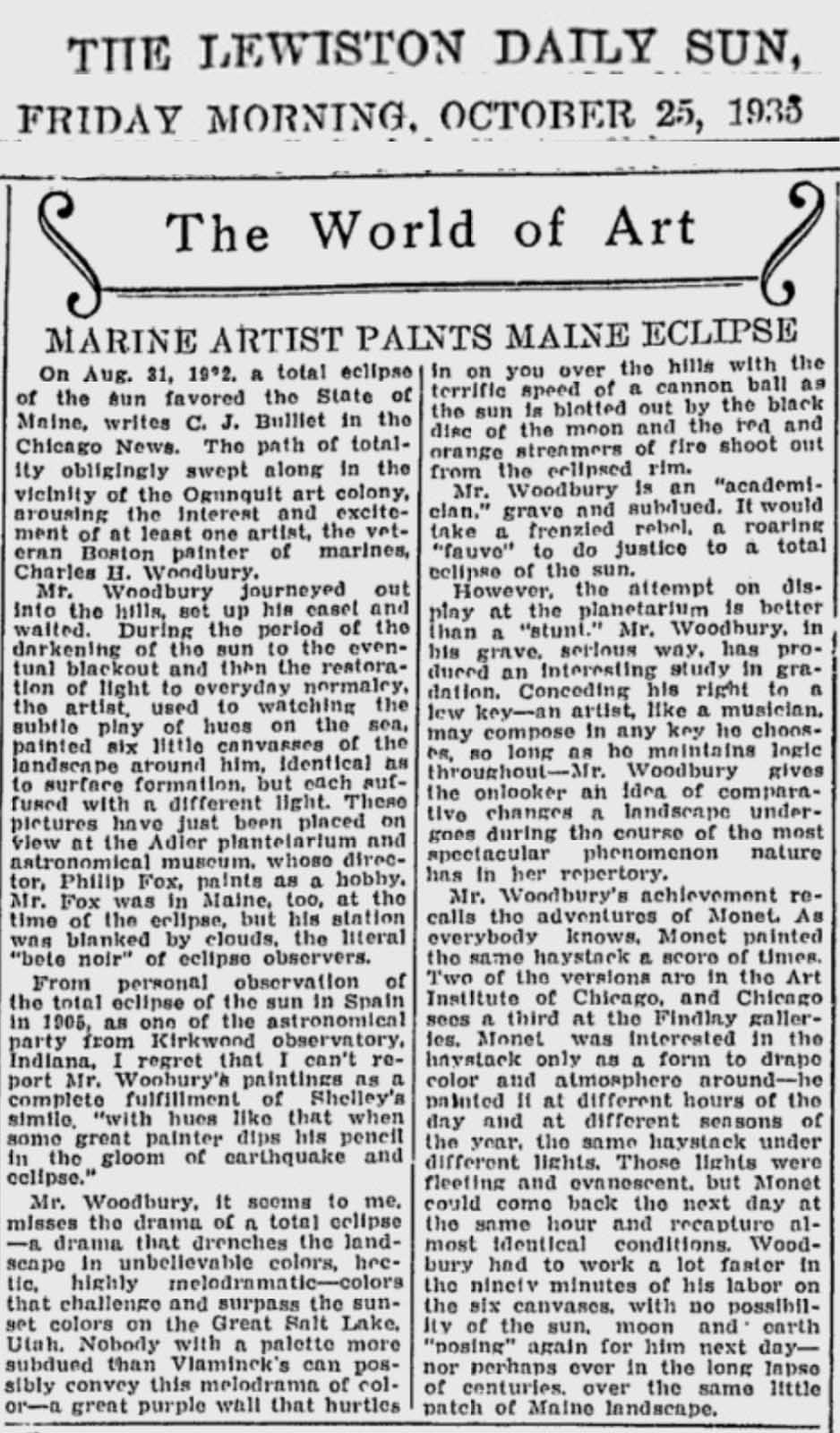

In 1935, the Lewiston Daily Sun ran a review of Charles H. Woodbury’s 1932 eclipse paintings by a Chicago-based art critic while the paintings were on display at the Adler Planetarium.

On Aug 31, 1932, a total eclipse of the sun favored the State of Maine, writes C. J. Bulliet in the Chicago News. The path of vitality obligingly swept along in the vicinity of the Ogunquit Art Colony, arousing the interest and excitement of at least one artist, the veteran Boston painter of marines, Charles H. Woodbury.

Mr. Woodbury journeyed out into the hills, set up his easel and waited. During the period of the darkening of the sun to the eventual blackout and then the restoration of light to everyday normalcy, the artist, used to watching the subtle play of the hues on the sea, painted six little canvases of the landscape around him, identical as to surface formation, but each suffused with a different light….

I regret that I can’t report Mr. Woodbury’s paintings as a complete fulfillment of Shelley’s simile, ‘with hues like that when some great painter dips his pencil in the gloom of earthquake and eclipse.’

Mr. Woodbury, it seems, misses the drama of a total eclipse — a drama that drenches the landscape in unbelievable colors, hectic, highly melodramatic — colors that challenge and surpass the colors on the Great Salt Lake, Utah. Nobody with a palette more subdued than Vlaminck’s can possibly convey this melodrama of color — a great purple wall that hurtles in on you over the hills with the terrific speed of a cannon ball as the sun is blotted out by the black disc of the moon and the red and orange streamers of fire shoot out from the eclipsed rim.

Mr. Woodbury is an ‘academician,’ grave and subdued. It would take a frenzied rebel, a roaring ‘fauve’ to do justice to a total eclipse of the sun.

However the attempt on display at the planetarium is better than a ‘stunt.’ Mr. Woodbury, in his grave and serious way, has produced an interesting study in gradation. Conceding his right to a low key — an artist, like a musician, may compose in any key he chooses, so long as he maintains logic throughout — Mr. Woodbury gives the onlooker an idea of comparative changes a landscape undergoes during the course of the most spectacular phenomenon nature has in her repertory.

Mr. Woodbury’s achievement recalls the adventures of Monet. As everybody knows, Monet painted the same haystack a score of times… Monet was interested in the haystack only as a form to drape color and atmosphere around — he painted it at different hours of the day and at different seasons of the year, the same haystack under different lights. Those lights were fleeting and evanescent, but Monet could come back the next day at the same hour and recapture almost identical conditions. Woodbury had to work a lot faster in the ninety minutes of his labor on the six canvases, with no possibility of the sun, moon, and earth ‘posing’ again for him the next day — nor perhaps ever in the long lapse of centuries, over the same little patch of Maine landscape.[6]

But Woodbury’s genius lay in his subtlety. Through his observations, he’d stumbled upon a scientific revelation. The light filtering through the moon during a total eclipse, he discovered, reversed the usual conditions, exhibiting a form of polarization. This groundbreaking observation, a testament to Woodbury’s keen eye, had never been documented by artists before. He had, in essence, used his art to make a scientific contribution.

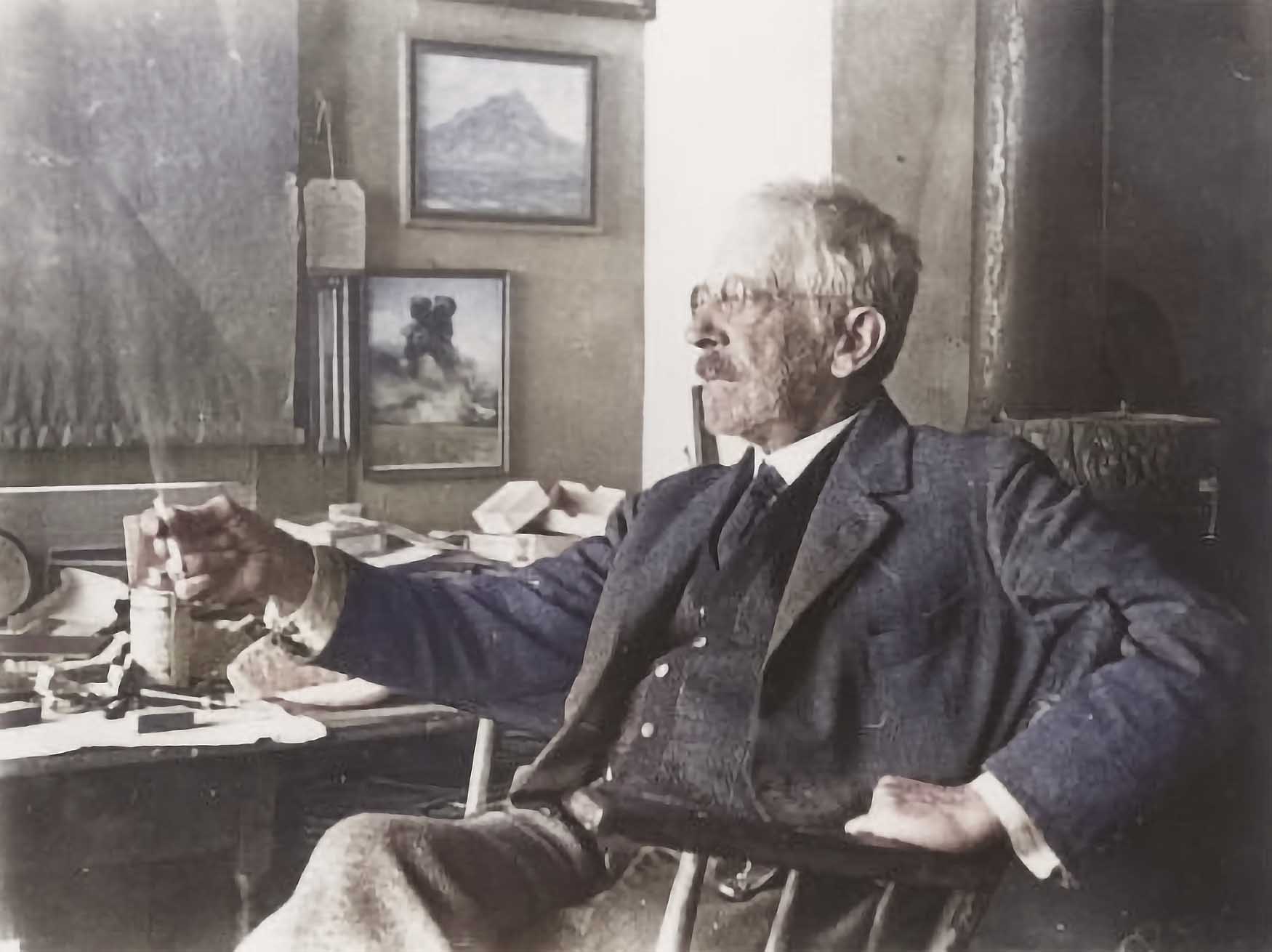

Charles Herbert Woodbury at his desk in 1935. (colorized)

These extraordinary paintings embody Woodbury’s pioneering spirit — and the think-outside-the-box ethos of the Ogunquit Art Colony. The paintings stand as a unique record of a celestial event, capturing the invisible and the fleeting through the power of observation and artistic expression. This story exemplifies the transformative power of looking beyond the obvious, a lesson that continues to resonate with artists and scientists alike. Charles H. Woodbury’s eclipse series is a reminder that art can transcend aesthetics, pushing the boundaries of perception and scientific inquiry.

Eric J. Taubert; Fog Lifting Over the Charles H. Woodbury Studio, Ogunquit, Maine; limited 1/10); aluminum archival dye sublimation (matte) print; 30×20.

Even now, as visitors stroll through Perkins Cove, in the shadow of the Charles H. Woodbury Studio, they can’t help but feel the echoes of Woodbury’s brushstrokes in the shimmering light and shifting shadows. His legacy endures not only in his prolific array of timeless artworks but also in the spirit of exploration and innovation that continues to animate the Ogunquit Art Colony and the Ogunquit Art Association / Barn Gallery to this day.

References:

- Exeter News-Letter. (1932, July 22). Total Eclipse of Sun on August 31. Exeter, NH.

- Exeter News-Letter. (1932, August 19). Front Page. Exeter, NH.

- American Artist. Volume 28 (1964). United States: Watson-Guptill Publications.

- Kanak, J. (2016, January 22). York Library hosts Charles Woodbury exhibit: Works of iconic Ogunquit artist, educator celebrated. Portsmouth Herald [Newspaper].

- Loria, J., Woodbury, C. H., & Seamans, W. A. (1988). Earth, Sea and Sky: Charles H. Woodbury, Artist and Teacher, 1864–1940. Cambridge, MA: MIT Museum.

- Maine Artist Paints Maine Eclipse. (1935, October 25). Lewiston Daily Sun [Newspaper].

Disclaimer: Information is harvested (at time of publication) from publicly available sources and is deemed reliable but not guaranteed – any editorial content is solely opinion-based – availability, prices, dates, times, details, and etc are subject to change or withdrawal at any time and for any reason. All dimensions are approximate and have not been verified. All data should be independently verified.